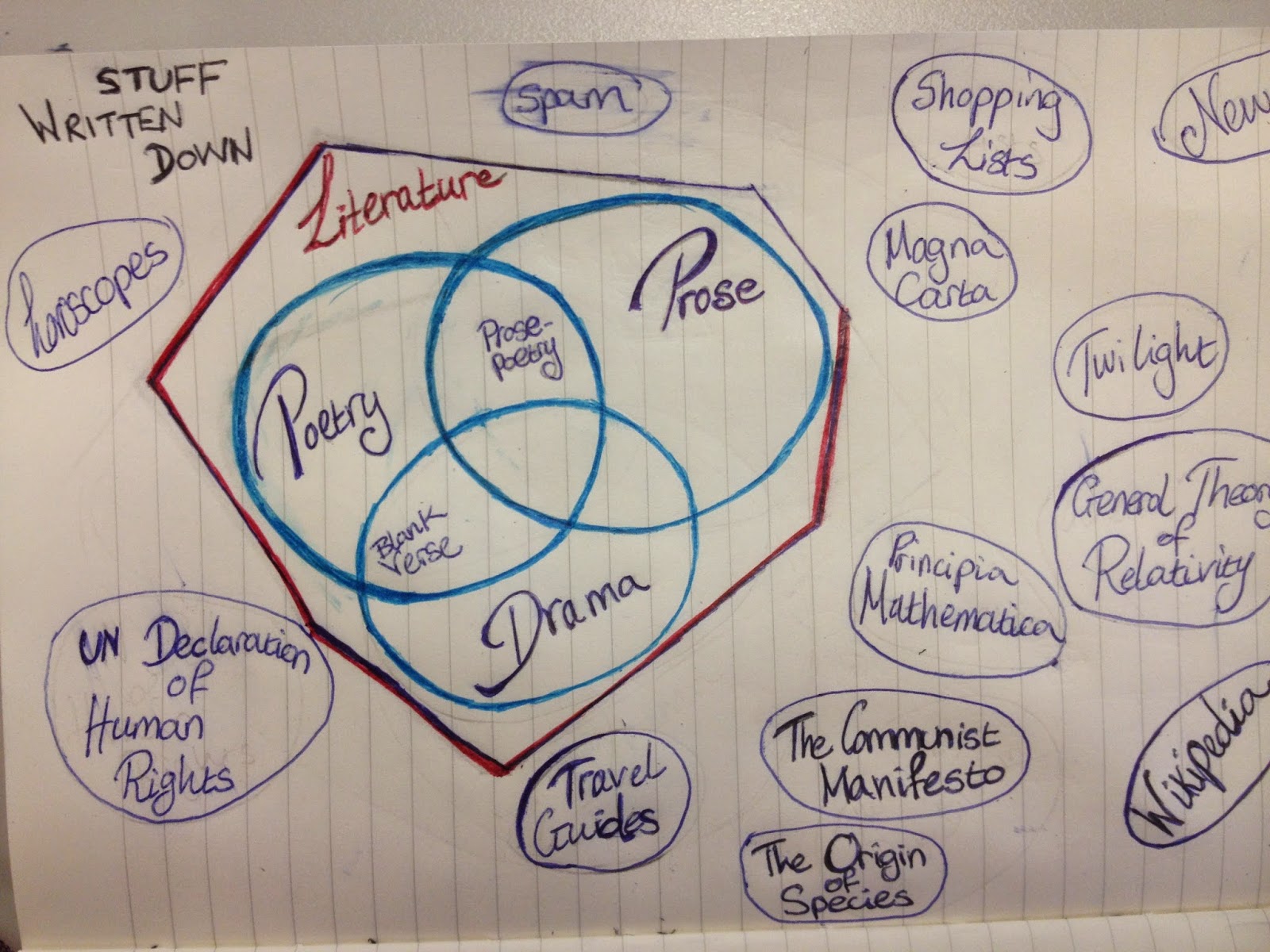

Lets start from the beginning. Most literature courses split texts into three categories: prose, poetry and drama. This can get confusing, because many plays are written in verse, and sometimes poems are written in prose, so essentially it is all lies. There is literature, and there is prose and verse and drama, but all these categories are porous, which means they are often more trouble than they are worth. Plus literature itself is not very clearly defined, but lets not even open that can of worms (yet). Here is a diagram to help place poetry:

There are some characteristics poems often have: the text is usually divided into lines, giving the poem a fixed shape on the page. Sometimes, these lines rhyme with each other; often this is in a repeating pattern. The poem is also likely to have a particular rhythm. This is not to say that a prose text or a play can't have a rhythm, or the odd rhyme. But in the case of poetry, often these things have a significant effect on the way we read the text, and influence the kind of meaning we extract from it.

Poets also tend to use poetic or literary devices. Again, these are not exclusive to poetry, but they tend to show up a lot more regularly in poems than in anything else. Here are some common ones:

Alliteration: repetition of the same consonant sound

Now the news. Night raids on

Five cities. Fires started.

Pressure applied by pincer movement

In threatening thrust. (W. H. Auden, 'The Age of Anxiety')

Assonance: repetition of the same vowel sound

Wee, sleekit, cow'rin, tim'rous beastie (Robert Burns, 'To a mouse')

(The trick with both alliteration and assonance is that they refer to the repetition of the sound and not of the letter. In English, because it would have been far too simple otherwise, there are multiple ways of spelling the same sound - a rough ruff, enough stuff, fluffy epiphany, shivering nation....

Rhyme: repetition of the same word-ending

Metaphor: saying one thing but meaning another:

The words in his book wormed off the pages. (Sylvia Plath, 'Suicide off egg rock')

in this example, the subject is losing control of his thoughts, or his thoughts are losing their meaning, as he prepares to commit suicide. There is no book.

Metonymy: using a part to refer to the whole or specific to refer to general

Simile: saying something is like something else

O my Luve's like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve's like the melodie

That’s sweetly play'd in tune. (Robert Burns, 'My Love is Like a Red Red Rose')

Personification: giving human qualities to something that is not human

When you notice a cat in profound meditation,

The reason, I tell you, is always the same:

His mind is engaged in a rapt contemplation

Of the thought, of the thought, of the thought of his name

(T. S. Eliot, 'The Naming of Cats')

Onomatopoeia: using words that sound like the sound you wish to convey (or inventing words that do). There is a whole poem full of examples:

So, now that those basic things have been explained, we can move onto poetic form, and try to establish what the point is in that. But I am rather tired, so that will have to wait till next time.

There are some characteristics poems often have: the text is usually divided into lines, giving the poem a fixed shape on the page. Sometimes, these lines rhyme with each other; often this is in a repeating pattern. The poem is also likely to have a particular rhythm. This is not to say that a prose text or a play can't have a rhythm, or the odd rhyme. But in the case of poetry, often these things have a significant effect on the way we read the text, and influence the kind of meaning we extract from it.

Poets also tend to use poetic or literary devices. Again, these are not exclusive to poetry, but they tend to show up a lot more regularly in poems than in anything else. Here are some common ones:

Alliteration: repetition of the same consonant sound

Now the news. Night raids on

Five cities. Fires started.

Pressure applied by pincer movement

In threatening thrust. (W. H. Auden, 'The Age of Anxiety')

Assonance: repetition of the same vowel sound

Wee, sleekit, cow'rin, tim'rous beastie (Robert Burns, 'To a mouse')

(The trick with both alliteration and assonance is that they refer to the repetition of the sound and not of the letter. In English, because it would have been far too simple otherwise, there are multiple ways of spelling the same sound - a rough ruff, enough stuff, fluffy epiphany, shivering nation....

Rhyme: repetition of the same word-ending

The way

was long, the wind was cold,

The

Minstrel was infirm and old;

His

wither'd cheek, and tresses gray,

Seem'd to

have known a better day;

The harp,

his sole remaining joy,

Was

carried by an orphan boy. (Walter Scott, 'The Lay of the Last Minstrel')

The words in his book wormed off the pages. (Sylvia Plath, 'Suicide off egg rock')

in this example, the subject is losing control of his thoughts, or his thoughts are losing their meaning, as he prepares to commit suicide. There is no book.

Metonymy: using a part to refer to the whole or specific to refer to general

watched my English teacher poke his earwax

with a well-chewed HB and get the class

to join his easy mocking of my essay

where I'd used verdant herbage for green grass.

(Edwin Morgan, 'Seven Decades')

Simile: saying something is like something else

O my Luve's like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve's like the melodie

That’s sweetly play'd in tune. (Robert Burns, 'My Love is Like a Red Red Rose')

Personification: giving human qualities to something that is not human

When you notice a cat in profound meditation,

The reason, I tell you, is always the same:

His mind is engaged in a rapt contemplation

Of the thought, of the thought, of the thought of his name

(T. S. Eliot, 'The Naming of Cats')

Onomatopoeia: using words that sound like the sound you wish to convey (or inventing words that do). There is a whole poem full of examples:

RUNNING

WATER (Onomatopoeia)

water

plops into pond

splish-splash

downhill

warbling

magpies in tree

trilling,

melodic thrill

whoosh,

passing breeze

flags

flutter and flap

frog

croaks, bird whistles

babbling

bubbles from tap (By Lee Emmett)

So, now that those basic things have been explained, we can move onto poetic form, and try to establish what the point is in that. But I am rather tired, so that will have to wait till next time.

No comments:

Post a Comment